End-of-year-lists: So arbitrary and yet so satisfying!

This year was a hard one for real reading. I would often sit down with a book and end up scrolling through the news on my phone in a daze for 45 minutes instead. So it goes without saying that there were a lot of books (too many books) that I wanted to read but failed to get to. But when I did manage to give a book my undivided attention this year, I was invariably rewarded. What a gift it is to be transported by good writing.

Here’s to more good reading in the year ahead. And in case you’re looking for something to read, here are my ten favorite newly published books of the year.

Temporary by Hilary Leichter

The absurdity of work-life can take almost infinite forms; I loved Hillary Leichter’s debut novel Temporary for making room for so many of them. This wonderful, whimsical tale is loosely about the search for stable work—in whatever form that might take. The unnamed narrator of Temporary floats through stints as a short-skirted office grind, a window washer, a murderer’s apprentice, a substitute mannequin, and even a human barnacle—all the while searching for “the steadiness.” I don’t want to deploy the tired, hollowed-out phrases “late capitalism” or “gig economy” to describe the subject of this book: Temporary is interested in something more subtle than any familiar economic critique can articulate. But still, it’s fair to say this book’s sideways preoccupations are all too relevant to the times we live in. (Full disclosure: I used to sit near Leichter when she worked at The New Yorker—in a temporary gig.)

Summer by Ali Smith

When I came to the end of Summer, I felt genuinely sad to have reached the conclusion of Ali Smith’s seasonal quartet, which has been a steady presence in my life since the release of Autumn in 2016. It feels like these books have managed to capture and distill something essential about the fragmented, disorienting times we’re living through. Is anyone else writing playful, searching, artistic novels about Brexit and Dominic Cummings and immigration detention centers and the coronavirus and the cratering British state? No, they are not. I wish we could find Ali Smith a few more seasons to meditate on.

The Street by Ann Petry

The Street sold 1.5 million copies when it was first published in 1946, but I’d never heard of it until Tayari Jones sang its praises in a 2018 The New York Times essay—citing its power both as a dramatic “tale of violence and vice” and an “uncompromising work of social criticism.” Recently republished in the U.K., the novel follows the travails of Lutie Johnson, a newly single mother in the prime of her life. After moving into an apartment of her own with her son, Lutie is hopeful about the chance to start a new chapter. But dangers lurk on every corner of her Harlem street: a creepy super, a scheming Madam, a sleazy nightclub owner (the list goes on). Watching the walls close in on Lutie—and seeing her defiance in the face of the odds—I was anxious and hopeful, gutted and enthralled. “I just can’t figure out why this work is not more widely read and celebrated,” Jones wrote. Me neither.

The Shadow King by Mazaa Mengiste

I knew next to nothing about the legacy of Italian imperialism in Ethiopia when I picked up this beautiful, poetic novel. The Shadow King takes place during the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, which began in 1935; as Mussolini’s troops invade Ethiopia, rural fighters boldly rush to Emperor Haile Selassie’s defense. Reading The Shadow King was an education for me—but also, an experience of pure art. As Mengiste recently explained on the FT’s Culture Call podcast, the book grew out of a chance encounter she had in Italy with a man who tearfully entrusted her with pages of his father’s photographs, diary entries, and letters about his time as a pilot in Ethiopia. Those documents sent her on a historical and imaginative journey. The resulting novel, which focuses in particular on the strong-willed women warriors who rose up to defend their country, and a Jewish-Italian soldier who photographs the war’s horrors, is a haunting masterpiece.

Uncanny Valley by Anna Wiener

When Anna Wiener started working in publishing, it didn’t take long for her to realize that the entire industry was slowly collapsing on itself. Her response was to flee to Silicon Valley. This is Wiener’s memoir of the series of the startup jobs she held in San Francisco in her twenties—a chronicle of her attempt to crack the rules of success in the tech industry. It might not shock you to learn those rules don’t actually make much sense, but that’s a key part of what gives this book its charm. Uncanny Valley is filled with sharp humor and well-earned ambivalence. The very act of writing suggests a kind of hopefulness too. We’ve given Big Tech so much power as a society—shouldn’t we all be able to muster the collective will to take that power away too?

The Cheapest Nights by Yusuf Idris, translated by Wadida Wassef

This newly republished book of short stories by Egyptian writer Yusuf Idris is a fantastically vivid portal into the lives of 1930s working-class Egyptians. There are maids and prostitutes, imams and undertakers, most of whom are faced with ugly daily conundrums as they navigate poverty. As Ezzedine Fishere writes in the book’s foreword, Idris’s writing is “above all about the complexity—and individuality—of suffering.” And unsurprisingly, it’s women who bear the brunt of the suffering in these stories. But these are more than stories of surviving hardship—they’re lively tales of comic deception, innocence, passion, and all the little things that color daily life.

The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett

A novel concerned with the constraints and opportunities offered by the shade of one’s skin felt, oh, particularly apt this year. The Vanishing Half follows the fates of twin sisters Stella and Desiree, descendants of the founder of Mallard, Louisiana, a town for light-skinned blacks. Inseparable in childhood, the sisters’ fates splinter in early adulthood, with profound consequences for the next generation. There are obvious lessons here about skin color and destiny in America, but also equivocal reflections on what it means to claim your own identity and forge your own path. Ultimately this book is a bittersweet, deeply absorbing fable about belonging, violence, and the myth-making we all engage in.

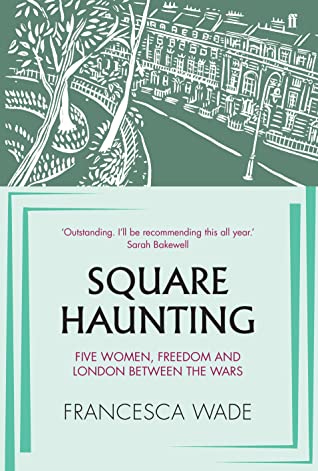

Square Haunting: Five Women, Freedom and London Between the Wars by Francesca Wade

The title of this book of interconnected biographies comes from a diary entry Virginia Wolf made in 1925 on the joys of “street sauntering and square haunting.” Here, the square in question is Mecklenburgh Square in Bloomsbury, a place where single women could safely rent affordable rooms, giving them the opportunity to live and work independently. The brilliant and complicated women Francesca Wade profiles (who all spent time living in the square) are poet H. D., broadcaster and detective novelist Dorothy Sayers, classics scholar Jane Harrison, economic historian Eileen Power, and novelist Virginia Woolf. Their paths and passions varied enormously, but what these women shared was a steadfast commitment to defying the conventions of their times in pursuit of the chance to do meaningful artistic and intellectual work. We could all learn a thing or two from their tenacity.

The Lying Life of Adults by Elena Ferrante, translated by Ann Goldstein

The Italian master’s latest compact novel has all the signature elements her readers have come to expect: Intense adolescent friendships, too-heavy infatuations, disorienting sexual discoveries, searing betrayals, uncomfortable intellectual awakenings, and of course, the raw vitality of the city of Naples itself. I gobbled it up like candy. At the heart of the novel is an exploration of the art of the lie, because, as critic Merve Emre puts it, “growing up also involves learning how to cultivate a talent for deception.”

Notes from an Apocalypse: A Personal Journey to the End of the World and Back by Mark O’Connell

“What if now it’s especially the end of the world, by which I mean even more the end of the world?” Mark O’Connell writes in this well-timed essay collection. To be honest, I didn’t think I needed to read another book about the end of the world—I’d already read about bunkers in New Zealand, tourists in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, preppers of all stripes, and so on. But this isn’t strictly a book of journalism—O’Connell’s reportorial journeys, instead, serve as a kind of vehicle for reflecting on our collective obsession with the end, and what it means to face a world that has been ending for a very long time. Wry yet earnest, these essays startled me with their humor and humanity. No book cheered me up and consoled me more this year.

Other new books I particularly appreciated in 2020: Island on Fire: The Revolt That Ended Slavery in the British Empire by Tom Zoellner, for its careful, remarkable account of an important chapter in history; The End of October by Lawrence Wright, for serving as a lively reminder that this year really should have just been fiction; A Woman Like Her: The Short Life of Qandeel Baloch by Sanam Maher, for its intriguingly unsatisfying portrait of an impossible-to-define woman; and Zadie Smith’s essay collection Intimations for its friendly companionship.

(And here are more previous lists: 2019, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2011 and 2010).

I really enjoyed talking about lions, bears, griffins, communes, murder, “the duality of glamour and catastrophe,” and other California specialities with writer Emma Cline and artist Walton Ford last week at the inaugural Gagosian Quarterly talk at The Greene Space. If you missed it, video of the event is now available:

I really enjoyed talking about lions, bears, griffins, communes, murder, “the duality of glamour and catastrophe,” and other California specialities with writer Emma Cline and artist Walton Ford last week at the inaugural Gagosian Quarterly talk at The Greene Space. If you missed it, video of the event is now available: